Written by Joe Ballenger

I wanted to dedicate another post to some of my other concerns about the pro-DDT movement. When I read posts which advocate DDT reintroduction in the US, a small amount of attention is paid to issues like how public health programs are run or the importance of resistance to DDT.

A great place to explore how all these things interact is by exploring the situation in India. Not only are they the biggest DDT using nation in the world, India has also made some really wonderful strides in combating malaria, having slashed infections by more than half over a 13 year period. They’ve got some really good scientists working on this problem, who thankfully publish very often.

So why did malaria rebound in India?

DDT Use and Malaria in India

Since I’m not an expert in the culture of India, I’d like to start out by quoting verbatim what Indian vector biologists have said about their situation. This is from a well-cited review, published in 2008:

The Global Malaria Eradication Programme of WHO launched in the 1950s was a huge success in India as the [malaria] incidence declined from estimated 75 million cases and 8,00,000 deaths in 1947 to just 49,151 cases and no deaths in 1961 and malaria was thought to be on the verge of eradication. It was then, that a series of setbacks were witnessed leading to malaria resurgence in multiple foci in the country and reported cases increased to 13,22,398 by 1971 and then to 64,67,215 in 1976.

The failure was attributed to the complacency, administrative, operational and technical problems like resistance in vectors to commonly used insecticide DDT and in parasites to chloroquine and overall low priority malaria enjoyed in the post control period.

In India, between 1952 and 1962, DDT caused a decrease in annual malaria cases from 100 million to 60,000. By the late 1970s, no longer able to use DDT, the number of cases increased to 6 million.

Those are…two very different statements.

One of the most detailed historical reviews I’ve found, one by VP Sharma does discuss shortages of DDT. In the review he does say that interruptions in the supply of DDT from the US, inefficient locally produced DDT sources, and difficulties in purchasing outside sources of DDT as reasons which helped malaria rebound. However, and this is important, Sharma does not say that this was the sole reason malaria rebounded.

At the time, India’s health services were under-staffed, and workers not properly supervised. This caused significant delays in testing for malaria, which kept health workers from detecting malaria when it first showed up in a new region. These chronic testing backlogs lasted months, and sometimes kept millions of people waiting for results. They simply didn’t have a way to efficiently target what few resources they had, because they had no idea where malaria was and when it was showing up.

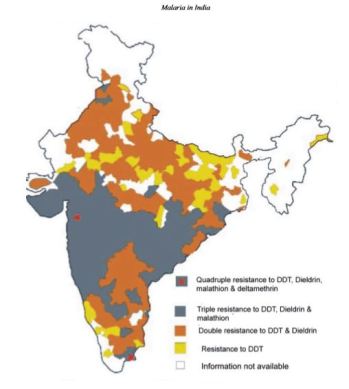

The pesticide resistance situation in India today is…not good. Resistance to DDT is widespread, and most places have mosquitoes that are resistant to more than one pesticide. Image Credit: Dash et. al 2008

At the same time, the biology of the vectors themselves was also changing. DDT resistance in Indian malaria vectors was first detected in 1959, and control failures due to DDT resistance started in the 1970s.

This caused some major difficulties in control as pesticide resistance genes eventually spread to other states. As the population with a need for malaria control grew, other pesticides had to be introduced. Eventually four other pesticides were introduced (HCH, Malathion, Dieldrin, and deltamethrin)…and the mosquitoes became resistant to these pretty quickly.

The pesticide resistance situation in India today is, well, it’s not good. Over most of the country, the main vectors are resistant to at least DDT. Resistance to DDT, dieldrin, and malathion is also common. Some vectors are resistant to the most commonly used groups of pesticides…all at once.

According to Sharma, in the 1960s, malaria was considered a non-issue and public health programs began to shift resources. As these problems were emerging, funding for malaria research was now competing for funding and personnel with yet another WHO program…the smallpox eradication program.

Mosquito Control in the Modern Age

India still has malaria, but the reasons India still has malaria are far more complicated than a lack of DDT. Many of the issues encountered in India, from the under-staffed medical facilities, to the shifting of resources to combat other health issues, were also seen in the worldwide WHO campaign.

The main issues facing mosquito control in India today are mostly administrative. India still doesn’t know how exactly bad its malaria problem is, because a lot of these issues occur in remote areas without access to healthcare. Many times, malaria is spread as sick people migrate from one region to another. On top of all this fewer people are going into vector control, which means that these pesticides are increasingly being applied by people who don’t know how to properly operate the equipment.

That latter one is a surprisingly big problem, by the way. People often refuse DDT spraying because it stains their walls, and because vector control people regularly act unprofessionally. Getting community buy-in is a real issue in some areas.

By fixating so much on one particular management tactic, Raptor and Offit do malaria scientists a disservice by giving the public the impression that mosquito control is a simple matter of applying a single pesticide and solving the problem for good. That’s the attitude which got us to today’s resistance situation.

Over the years, entomologists have realized that we need to use a variety of tools to fight disease. There isn’t just one tool that we need, we need dozens.

The problem we’re facing isn’t the lack of DDT…it’s the lack of tools.

Where do Economics Come Into Play?

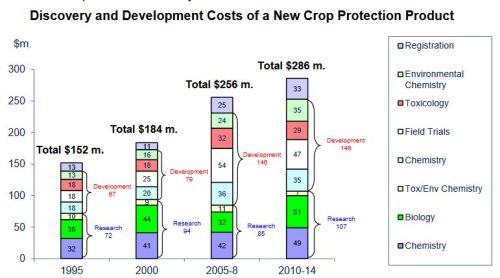

There’s a surprising link between vector control and agriculture. Most of the pesticides used in vector control were originally intended for use in agriculture, and a select group which were relatively OK to apply somewhat close to people were selected to control mosquitoes. In recent years, the rate of new pesticide introductions has gone down across the board. This is because the process has become more expensive, mostly due to the cost of tests required to go through the regulatory process.

While the average time of discovery has stayed at about 4 years, the number of compounds which need to be screened to get an acceptable product have risen from 15,000 in 1980 to more than 150,000 in 2000. This hasn’t changed much since then, either. The pesticide industry has hit a plateau, according to industry data.

How much it takes to get a new pesticide to market, based on industry data from CropLife International.

Mosquitoes are not getting easier to manage, mostly due to biological factors. At the same time, the cost of pesticide development is increasing. To develop a new type of pesticide, it costs $250 million and can take between 8-12 years to get it registered for sale.

After this initial investment, the product never becomes more effective. All types of pest control eventually develop resistance, and become less effective over time. Compared to agriculture, mosquito control is a relatively small market…which makes it really hard to get new mosquito control compounds on the market.

The Bottom Line

With India, we’ve gotten a window into what mosquito control is like in the country that produces most of the world’s DDT. They’ve still got issues with malaria, but only partially because because the US stopped producing DDT. Complacency, difficulties in tracking epidemics, competition for resources with other programs, and difficulties caused by pesticide resistance also played a major historical role.

…but the question I’ve been asked is whether reintroducing DDT in the US is a good idea based on the reasoning of Paul Offit and Skeptical Raptor. So let’s focus on the core of the argument as it pertains to management of Aedes in the US for Zika control.

I feel that the problem with Raptor and Offit’s line of thought is that they implicitly assume that DDT will be as effective as any other new product on the market. Before we even start talking about DDT, they’ve already begun ignoring the more recent lessons of mosquito control that we’ve discussed here.

The fact that DDT kills mosquitoes is true. It’s still widely used, it’s been used to combat resistance to other pesticides in malaria vectors, so it’s something which shouldn’t be phased out. The problem is that DDT is also an old pesticide, which has been used around the world for a long time. Because it’s been used so extensively, it’s built up a lot of resistance in a lot of mosquito populations.

In the US, Aedes mosquitoes are resistant to DDT. The resistance isn’t much, only two-fold, probably not enough to cause treatment failure, but there’s already a baseline resistance to DDT in one of the vectors the Skeptic community is telling us to control using DDT. Around the world, many Dengue programs have failed because of resistance to DDT in the main mosquito vectors. DDT resistance in Aedes mosquitoes is a well recognized problem, and it’s one the US has despite the fact we don’t use DDT.

The other problem, which Raptor didn’t discuss, is how mobile Aedes mosquitoes are. Aedes hops around the planet by shipping activity, which means it’s only a matter of time before one of those highly resistant genotypes arrives. Malaria mosquitoes are regional, Aedes mosquitoes are international.

If we were to attempt to re-register DDT, assuming no political backlash, it would likely have to go through a regulatory process similar in extent and cost to a newer pesticide. Appeasing new regulations, determining effectiveness…mundane stuff like that. It doesn’t matter if those regulations are more strict than they are now, less strict than they are now, or the same…the US regulatory process would likely treat it the same as any other potential pesticide.

Economically speaking, this is the real problem with DDT. We already know that it’s less effective than the newer things coming on the market, because new pesticides don’t come saddled with resistance issues that are nearly worldwide in scope. Objectively speaking, it’s just not a good use of resources to reintroduce it after 70 years of worldwide use because we wouldn’t see the same benefits we’d see if we put those efforts into developing and promoting newer tools.

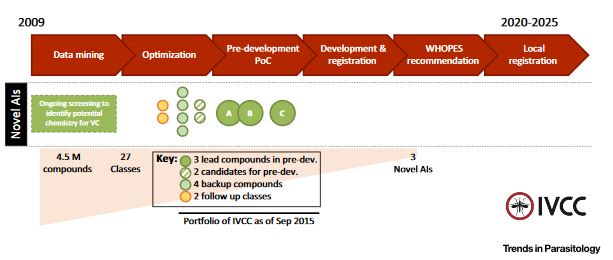

While Raptor and Offit are putting considerable effort into advocating for something that will likely fail sooner rather than later, scientists are struggling to introduce the next generation of useful mosquito control tools. There’s a group called the Innovative Vector Control Consortium, which has partnered with industry groups and public health officials to develop the new tools needed to control mosquitoes which spread diseases like malaria and Zika.

Progress of IVCC projects, as of 2015. Developing new pesticides is a slow process, but it’s still humming along. Image Credit: Ranson and Lissenden, 2016

I genuinely want to move this process forward, so I choose to advocate for the scientists at groups like the IVCC that are doing the difficult work of developing those tools. I just don’t think advocating for DDT is a great idea, when there are many more promising tools on the horizon.

Works Cited:

Singh, R. K., Dhiman, R. C., Mittal, P. K., & Dua, V. K. (2011). Susceptibility status of dengue vectors against various insecticides in Koderma (Jharkhand), India. Journal of vector borne diseases, 48(2), 116.

Sparks, T. C. (2013). Insecticide discovery: an evaluation and analysis. Pesticide biochemistry and physiology, 107(1), 8-17.

Disclosure: Joe Ballenger works as a contractor at a company which develops pesticides.

Wow. That’s thorough.

It’s a tough fight, correcting the political errors of the past 20 years, but somebody’s got to do it. I added this article to my index of key DDT sources at my blog.

LikeLike