Written by Joe Ballenger

So…this is a correction of a previous post I wrote on Facebook, back in March.

In the comments under the article, I may have gotten myself into a bit of trouble because I made some comments which implied some things which weren’t quite correct:

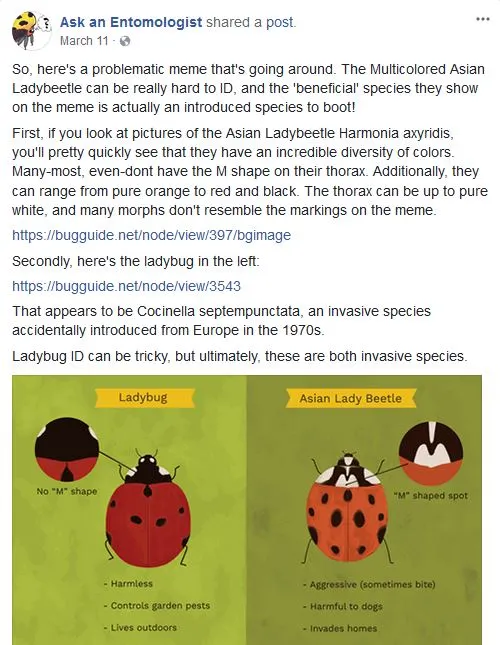

Everything here is factually correct. Ladybugs bought online don’t really help with pest control, unless they’re contained inside the garden with something like netting. Invasive ladybugs do carry parasites, whose roles in ladybug ecology are uncertain overall. They also do eat ladybug eggs and larvae, and it’s that last point which I’ve decided to explore a little bit further.

When I made these comments, the implication…and what I thought was true at the time, was that Asian ladybeetles were a major cause of ladybug species changes in North America. However, it seems that I wasn’t current in my research because these questions have begun to be answered by our colleagues.

So…this week, let’s explore ladybug declines in the US.

Starting at the Beginning

In the 1870s, the first successful introduction of an insect predator saved the orange industry. Since the agent was a ladybug, it was thought that naturally ladybird beetles would be good control agents.

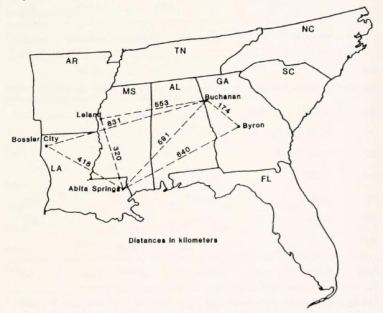

There were some successes, with the Multicolored Asian Ladybeetle providing some control of aphids in tree cropping systems. Small releases were made across the US, between the 1920s and 1980s, and it was thought to be a species that didn’t easily establish. However, in the 1988, someone running a mercury vapor light in Abita Springs, Louisiana (there’s a famous brewery there, interestingly) caught thousands of ladybeetles in their light trap…and that’s when it became apparent there was a new invasive strain in the US.

One of the things I’ve always been interested in was whether the introduction of this invasive strain was connected to the strains released by early biocontrol workers. I’ve actually lived in this area, and can attest that the closest release site (Leland, MS) is about half a day’s drive from Abita Springs. The releases occurred from 1978 to 1982, well before the 1988 discovery. Furthermore, there’s at least four major agricultural universities in this area which would be routinely on the lookout for new pests. So far as I-or anyone can tell-it’s likely this particular strain came in on shipping containers.

Useful in Agriculture?

The Multicolored Asian Ladybeetle has been useful in controlling pests in a number of crops, namely pecans, pines, and soybeans. They’re a very hardy ladybug, and can often withstand pesticides better than their prey can. They’re good at avoiding predators, but there are things which eat them. They’ll also eat a lot of different bugs, from aphids to ladybirds.

However, at the same time, these insects themselves are pests as well. They’re well recognized household pests, and we get dozens of emails about them every fall and spring because that’s when they’re around people. However, on farms, they’re also problematic because they can mix in with fruit and ruin the taste of fruit juices with their defensive chemicals. They also eat the fruit before winter, which opens up the fruit to contamination from other stuff.

They’re particularly damaging in the wine industry, where their characteristic flavor has been given the name ‘ladybug taint’.

Ladybug Declines

So, needless to say, our relationship with these insects is a little bit complicated. They were introduced because we thought they’d make a good replacement for ladybirds which were doing a poor job of controlling pests in agricultural fields, and then subsequently became pests in other contexts.

…but what about their relationships to other ladybug species? How can we get to the bottom of that?

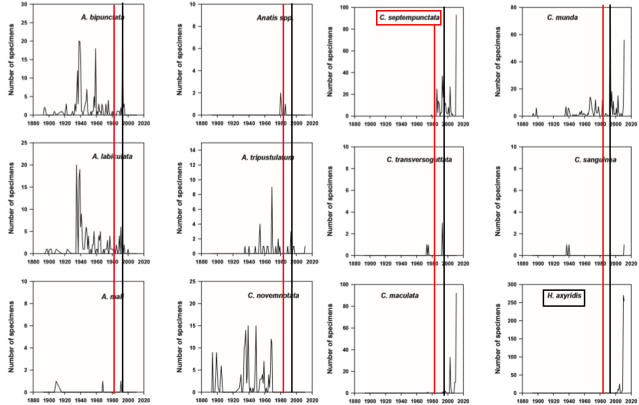

Well, one of the things we can do is to look at when various invasive species arrived in an area, and compare them to data gathered from insect museums. The idea here is to see if there’s a correlation between changes in the ladybug population, and when the invasive species arrived.

To make it easier to interpret the data from these graphs, I’ve highlighted the years that two invasive ladybug species arrived. The 7 spotted ladybird, Coccinella septempunctata, native to Europe, is highlighted in red. The Multicolored Asian Ladybeetle, Harmonia axyridis, has been highlighted in Black. In both cases, the big changes for many of these species happened well before the arrival of these species in Missouri.

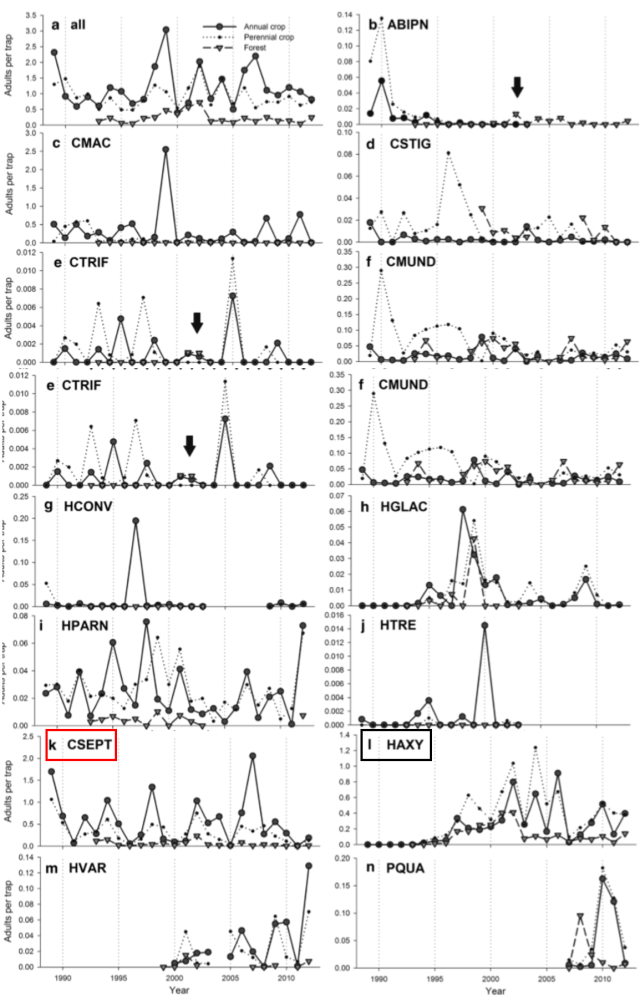

Another thing we can do is to look at these sorts of correlations in the habitats where these insects hang out. This not only cues us into these sorts of correlations, but tells us if the ladybirds appear in the same time and place. This was done by trapping native and exotic ladybirds at a research site in Michigan, which was surrounded by two different types of agricultural systems and forests.

Again we generally see a lack of a correlation in ladybug declines, except for Adalia bipunctata (ABIPN) and Coleomegilla maculata (CMAC). Where there are declines, they’re usually correlated with a change in habitat. The Multicolored Asian Ladybeetle tends to like perrenial crops (like apples) and annual crops (e.g. soybeans), while the 7 spotted ladybeetle tends to hang out more in annual crops (although it’s found in both types of crops). For the most part, there seems to be a peaceful coexistence.

The Bottom Line

Figuring out why-and if-ladybugs is declining is a complicated affair. In some cases, they aren’t actually declining. In other cases, they are declining…but it’s a part of a natural boom and bust cycle that’s a part of nature.

In the cases where there are real declines that can’t be explained by competition or natural cycles, it’s usually because of changes in habitat use. Ladybugs are frequently found in agricultural settings, but they need natural spaces (or refuges) in order to lay eggs. It used to be that there would be borders around farm fields, hedgerows which would provide these refuges. However, as agriculture has become increasingly automated, farmers now have the precision needed to farm the areas which used to house these refuges.

Conservation is a complicated affair, and it only becomes more complex when ecological factors are put in the mix. Pest control provided by these sorts of natural predators is an important part of agriculture, and new farming techniques can be used to enhance other pest control measures. There needs to be a way for these sort of natural areas to become more widely viewed as profitable, even though many farmers do already understand the benefits of natural pest control. That’s a more complicated conversation which deserves it’s own blog post, though.

For now…it appears that invasive ladybirds aren’t as large of a factor in the decline of native ladybug species.

Works Cited

The multicolored Asian lady beetle, Harmonia axyridis: A review of its biology, uses in biological control, and non-target impacts

Pingback: Ladybugs Wind Sail into the Hills - Following Deer Creek

Hello! I have noticed a ladybug on the ground in the park yesterday and let it climb on my hand. It stayed on my hand for a while, longer than ever, it didn’t fly away! I was surprised, but it stayed even when I went to class, later when I was in the bus and in the tram. It walked around on my hands but wouldn’t fly away. In one moment it fell of on the ground (0.5 meters height) and some lady who was walking behind me, went over it with her travelling bag (not with the wheels). So I picked it up and continued my way home. On the way, it started heavily raining, and I couldn’t leave it anywhere. I felt sorry for the ladybug. There is definitely something wrong with it because it won’t fly. It stayed on a plant in my apartment since yesterday and I’ve put some wet paper towel bit on it, few drops of water and some honey on a lid of a glass container, also a peace of lettuce just in case with a tiny dead bug on it. I’ve put it next to the offerings. I haven’t seen it use any of it. Sometimes it moves but mostly it has stayed on the plant. Also, it kind of does the thing when it randomly licks its hands… I’m worried about it and I don’t want it to die. I want to take it outside but again I’m worried what will happen since it doesn’t fly. I don’t know what species it is but it looks like a regular ladybug to me. I’m struggling to find a place online to ask a question, it’s all FAQs, already answered questions. Was it a mistake bringing it home with me? How can I take care of it? How can I help it fly? Could it be due to some damage? Any advice? I can send pictures.

LikeLike

I wouldn’t worry too much. If you’re worried, I would honestly release it back into the wild. Lady beetles have short lifespans compared to us. More time outside means that they are more likely to find a mate and reproduce.

LikeLike

We have had hundreds of lady beetles surround our house and vehicles. They have got inside even though we have insect screens. It has been months since they arrived. How can we reduce the population in the house?

LikeLike