In the recent few weeks, the news has been filling up with stories about a new epidemic called Zika virus. Since it’s a hot topic, and potentially very important, I wanted to write something explaining what this virus is from a variety of perspectives.

We’ll get into this more during this post, but this is a giant ‘Oh, sh*t’ moment for public health. Before the events in Brazil, Zika virus was considered an obscure disease. People got sick, but it didn’t appear to kill anyone and it’s effects seemed to be transient. The reported connection to birth defects came as a complete shock to many, and quite frankly there’s no way anybody could have predicted this.

So let’s explore the biology of this virus, and the history of this disease.

What is Zika virus?

Rhesus Macaque, looking about like I did when I started reading about Zika virus. Image credit: Einar Fredriksen License info: CC BY-SA 2.0

To understand what Zika virus is, you need to understand how we know this virus exists. There are a lot of scientists who monitor for new viruses using what are called sentinel animals, which are caged animals placed in areas where it is suspected that viruses are circulating. Sometimes, these animals get sick with something new…and that’s how new viruses are often discovered.

In 1947, Zika virus was discovered in a caged Rhesus Macaque. This is a type of monkey used for surveillance purposes. It was quickly found in local mosquitoes, Aedes africanus, and isolated from some of the local people. It was initially thought to be a minor, local, disease which circulated mostly in monkeys and sometimes accidentally got into people.

When it gets into people it causes a fever, rash, pinkeye, and joint pain. These are all very mild symptoms, and are very similar to some other diseases which are closely related. Dengue and Chikungunya can cause all of these symptoms, so Zika really needs to be diagnosed by using antibodies or looking for genetic material from Zika.

The virus was a very obscure for the longest time, until a few years ago when it showed up in Brazil. There was some work which was done looking at potential vectors, looking for animals it showed up in, and to see what Zika was related to. However it didn’t appear to kill anybody, so more attention was paid to other diseases like Dengue Fever.

How did Zika get to Brazil?

@BugQuestions I’ve seen respectable minds disagree over reason for zikas rapid advancement; is climate change or globalization more likely?

— Jimmy Conway (@InsectophileJim) January 28, 2016

So you have this virus which was found in the 1950s in the Zika forest in Uganda, and now it’s in Brazil. The virus doesn’t get transmitted through the air, and barely lives outside the body. The mosquito which transmits the disease doesn’t migrate across the oceans. So, on the surface, it can seem kind of confusing as to how the disease can start spreading on four continents.

Aedes mosquitoes are the vectors for Zika virus. Aedes aegypti, shown on the left, is the main vector. Aedes albopictus, on the right, has been implicated as being a main vector in some outbreaks but is considered a poor vector of the disease.

Before this epidemic, about 300 years ago, Ae. aegypti hopped around the globe by following people. Ae. albopictus followed it in very much the same way a couple hundred years later. Both of these mosquitoes have different home ranges, with Ae. aegypti originating in Africa and Ae. albopictus coming from Asia. Ae aegypt feeds mostly on people, which makes it a good vector. Most populations of Ae. albopictus are generalists, which means it’s not a very good vector.

Before the virus made it out of Africa, the stage was set for this epidemic by globalization. Dengue and Yellow Fever, which are similar to Zika (we’ll discuss this later), has been circulating in the Americas since the 1800s. Viruses hopping from Africa to America have happened before.

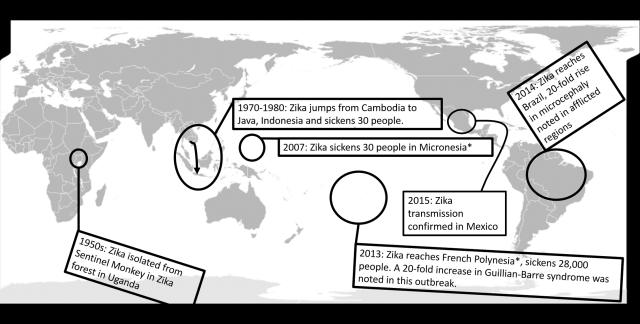

Simplified timeline of Zika outbreaks, in relation to geographic area. Asterisks denote approximate locations. Map image credit: Lokal_Profil, via Wikimedia commons. License info: Public domain. Image modified to show timeline of Zika transmission by Joe Ballenger

The first recorded outbreak in the literature appears to have happened in Indionesia, where 30 people were diagnosed with Zika in 1978. In the nearby islands of Micronesia, the 30 people became ill with the virus in 2007. In the year 2013, the virus reached French Polynesia and sickened an estimated 28,000 people. The virus reached Brazil in 2014.

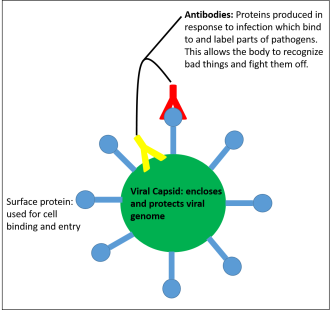

Antibodies are molecules which bind to, and label, foreign organisms which get into people. They’re really useful for determining whether people have been exposed to certian pathogens, because they have to be cued into a particular organism.

Mapping the jumps from Africa to Africa to the South Pacific is a little tricky using the outbreaks alone, however there were also scientists looking for viral antibodies in people all over the world. Anti-Zika antibodies have been found in people living in Cambodia, and the virus has also been isolated from that region despite lack of apparent outbreaks. The virus which caused the South Pacific outbreaks appears to have come from Cambodia. However, it appears these studies haven’t been done on the virus circulating in Brazil (more likely, they just haven’t been published yet).

The question raised by Jimmy Conway at the top of this paragraph, I think is a key question. On the surface, it appears that Zika came out of nowhere. However, many papers on the subject note the similarities in the symptoms of very mild Dengue infections and infections by Chikungunya. In many cases, Zika was misdiagnosed as either of these two diseases and the mistake wasn’t discovered until stored samples were analyzed years later.

So this outbreak didn’t happen in a vacuum, and the virus didn’t spontaneously appear in Brazil. It appears that many factors played a role here. Misdiagnosis may have masked Zika’s emergence, and many infections are so minor that people don’t even think to visit a doctor. Most people don’t even get visible symptoms. It also appears the range of the virus expanded from Africa to Asia, and jumped across the ocean. Presumably this happened in humans, but there’s also evidence the virus can infect rats. The roles of biology, climate change, and globalization aren’t entirely clear at this point.

What does Zika virus do?

The reason that Zika is becoming news is because of birth defects. The virus is believed to be linked to infants with a severe neurological defect called microcephaly. Infants with this condition are born with small heads, because they’re missing most of their brain. The story appears to be a lot more complicated than that, however.

To explore this story, we need to start small. Like, really small…and answer our first question again from another perspective.

What is Zika virus?

I know it seems like this is repetition, but the first time we answered this from the perspective of the medical community. Now, we’re discussing it from the perspective of a virologist.

Zika virus is in a group of arthropod transmitted viruses called Flaviviruses. Some of the other viruses we’ve talked about in this post, Dengue and Chikungunya, are also in this group. In fact, they’re transmitted by the very same mosquito species as Zika.

When an infected mosquito bites a human, the first cells these viruses infect are skin cells. From here, the path of infection is different. Dengue and Chikungunya infect white blood cells, but it isn’t really well understood what Zika virus does. It will infect skin cells in a petri dish, and it’s likely it does that during human infection. In mice, the virus somehow moves into the brain. That’s about all that’s known about how Zika virus infects people.

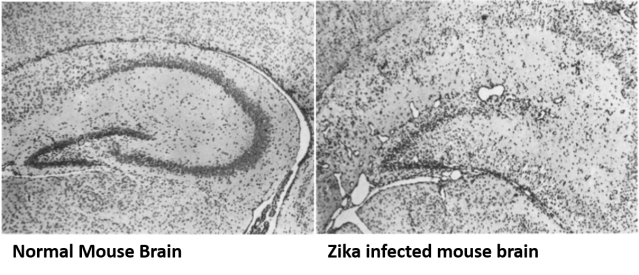

This is the scary thing about Zika, it appears to infect the brain. In the only paper I could find on this topic, it appears that virus was only replicated from the brain and no other organs. This is important because…

Zika appears to cause brain damage

A 17 year-old from Ghana who displays microcephaly, which may not be related to Zika. There are many causes for this disease, including pathogens unrelated to Zika virus. Image credit: Allison Stillwell Young, via Flikr License info: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Zika is in the news because of a drastic increase in microcephaly in areas of Brazil where the virus is circulating. There’s a very high correlation between these areas and the increase in microcephaly, but correlation isn’t causation. However, no other factors seem to be able to explain this increase…so Zika virus appears to be involved via Ockham’s razor.

Less attention has been given to another condition which has been linked to Zika. During the outbreaks in the South Pacific, an increase in another condition called Guillain-Barre syndrome was noted. Guillain-Barre is a rapid-onset paralysis which is caused by damage to the peripheral nervous system, and it’s something which can be fatal in severe cases.

So we’ve got a virus that appears to infect brain tissue, and outbreaks that correlate with two very serious types of brain damage. However, that appears to be all we really know. Why the South Pacific outbreak was linked to Guillian-Barre, and why the South American outbreak is linked to microcephaly isn’t clear. It could be that Guillian-Barre is being overlooked in South America, or it could be that an increase in microcephaly wasn’t noticed in the South Pacific outbreak. It could also be that different strains of the virus cause different problems.

Brain of mouse experimentally infected with Zika virus. Normally, the cells in this structure are organized and neat like on the left. During Zika infection, the cells become disorganized. Blood vessels also expand, and holes in tissue appear during viral infection. What happens in humans isn’t known at this point in time. Image credit: Bell, et. al 1971

There isn’t much data on how the virus causes damage, and that’s a part of the problem. It infects the brain, and destroys brain cells, so microcephaly and Guillian-Barre both make sense given this information. It’s unknown why so many people don’t show any symptoms when infected, and it’s also unknown whether there are is any other important type of brain damage which results from this infection.

The potential modes of transmission aren’t well fleshed out, either. There’s evidence that Zika can be transmitted sexually, and while this probably isn’t a major mode of transmission…it’s unknown how often this happens and whether neurological damage to a fetus or a person could happen from this route.

Nobody knows exactly what’s going on at this point because the notion that this virus causes massive outbreaks is so new that a lot of the epidemiological footwork which needs to be done…just simply hasn’t had a chance to be done.

How big of a threat is this virus to the US?

I think this is the big question, and frankly…I’m not sure how this will play out in the long-term. I don’t even want to speculate on that because I do agriculture and not public health.

What I do feel comfortable pointing out is that conditions between the US and Brazil are very different. Mosquito control here is easier for a number of reasons. In many regions, winter gives us about three to four months where mosquito-born disease can’t be transmitted. There’s also several months where mosquito populations are either increasing or decreasing, so transmission is lighter during those times. We also live in air-conditioned homes, with screens that separate us from the outside. Brazil is close enough to the equator as to where winter doesn’t happen, and seasons in many areas are a lot more uniform than many areas of the US. There’s also a lot of poverty in Brazil, so window screens aren’t common in many areas.

The US has a lot more resources we can dedicate to mosquito control, and the population dynamics of mosquitoes are different. Ae. aegypti, the main vector, is present in many states. However, Ae. albopictus, has a wider range within the US. The areas with Ae. albopictus probably won’t see as much transmission, due to the fact it doesn’t feed on people as much as Ae. aegypti.

While I think these things are worth mentioning, I think it’s also important to talk about ease of spread. How easily a virus can be spread is denoted by a number called the R0, which is different in each outbreak.

R0 is basically how many hosts a single infected host will infect on average. A disease needs to have an R0 of at least 2 in order to increase the number of infected people, and the job of an epidemiologist is to lower the R0 below 1 so the sickness eventually disappears.

The R0 of Zika, as far as I can tell from the literature, is unknown. Dengue, a similar virus, can have a R0 between 2 and 10…depending on the outbreak. However, given the fact that Zika only displays any sort of symptoms in 20% of infections, it’s possible that a Zika infection in the US would be harder to detect than Dengue.

So I’m not sure how big of a threat this virus is to the US over the long term, although I do believe that the increased surveillance measures and travel restrictions mentioned in the news are a good idea. The differences in mosquito species presence, climate, living spaces, and mosquito control measures, make me think that sustained transmission will be very difficult for Zika. Imported cases of similar diseases like Dengue do happen, but sustained transmission never takes hold for these reasons.

The Bottom Line

Zika is bad news, but with the exception of a few imported cases, it’s not in the US yet. That’s the important thing…if you’re in the US, you’re not at risk at this moment.

Zika is scary because it’s similar to other mosquito-born viruses, but different because signs of infection might not manifest until a child is born with birth defects. 4 out of 5 times, you won’t even know you have it. It’s also possible that someone could be infected, and have neurological damage which only manifests at a later date. There’s just not a lot of information out right now.

Fortunately, getting that information is what scientists do. We watch, we learn, we retrace our steps, and we figure stuff out. There’s a lot of research coming down the pike, and answers to a lot of these questions will come sooner rather than later.

For more information, pay close attention to the CDC and WHO pages on this topic.

Correction 2/3/2016, 10:44 PM: Guillian-Barre is caused by damage to the peripheral nervous system (e.g. spinal cord), and not the central nervous system (e.g. brain). Thanks to Alon Coppens to pointing out this mistake.

Works Cited:

- Bell, T. M., Field, E. J., & Narang, H. K. (1971). Zika virus infection of the central nervous system of mice. Archiv für die gesamte Virusforschung, 35(2-3), 183-193.

- Dick, G. W. A. (1952). Zika virus (II). Pathogenicity and physical properties. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 46(5), 521-534.

- Dick, G. W. A., Kitchen, S. F., & Haddow, A. J. (1952). Zika virus (I). Isolations and serological specificity. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 46(5), 509-520.

- Duffy, M. R., Chen, T. H., Hancock, W. T., Powers, A. M., Kool, J. L., Lanciotti, R. S., … & Guillaumot, L. (2009). Zika virus outbreak on Yap Island, federated states of Micronesia. New England Journal of Medicine, 360(24), 2536-2543.

- Fauci, A. S., & Morens, D. M. (2016). Zika Virus in the Americas—Yet Another Arbovirus Threat. New England Journal of Medicine.

- Faye, O., Freire, C. C., Iamarino, A., Faye, O., de Oliveira, J. V. C., Diallo, M., & Zanotto, P. M. (2014). Molecular evolution of Zika virus during its emergence in the 20th century. PLoS neglected tropical diseases, 8(1), e2636.

- Hayes, E. B. (2009). Zika virus outside Africa. Emerging infectious diseases, 15(9), 1347.

- Marcondes, C. B., & Ximenes, M. D. F. F. D. (2015). Zika virus in Brazil and the danger of infestation by Aedes (Stegomyia) mosquitoes. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical, (AHEAD), 0-0.

- Musso, D., Nilles, E. J., & Cao‐Lormeau, V. M. (2014). Rapid spread of emerging Zika virus in the Pacific area. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 20(10), O595-O596.

- Nishiura, H. (2006). Mathematical and statistical analyses of the spread of dengue. Dengue Bulletin.

-

Oliveira Melo, A. S., Malinger, G., Ximenes, R., Szejnfeld, P. O., Alves Sampaio, S., & Bispo de Filippis, A. M. (2016). Zika virus intrauterine infection causes fetal brain abnormality and microcephaly: tip of the iceberg?. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 47(1), 6-7.

- Olson, J. G., & Ksiazek, T. G. (1981). Zika virus, a cause of fever in Central Java, Indonesia. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 75(3), 389-393.

-

Patiño-Barbosa, A. M., Medina, I., Gil-Restrepo, A. F., & Rodriguez-Morales, A. J. (2015). Zika: another sexually transmitted infection?. Sexually transmitted infections, sextrans-2015.

Curious to hear (perhaps a follow up post?) what your, and other entomologists who study mosquitoes, reaction is to this Slate article:

http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/science/2016/01/zika_carrying_mosquitoes_are_a_global_scourge_and_must_be_stopped.single.html

LikeLike

A lot of the current panic is the result of two factors: the link to birth defects; and the drastic loss of tourism that Brazil is expecting (Carnival, the Olympics). A great deal of money stands to be lost at this point.

LikeLike

We kind of already tackled this in another post: What do Mosquitoes and Other Biting Insects Add to the Ecosystem (https://askentomologists.com/2015/02/02/what-do-mosquitoes-and-other-biting-insects-add-to-the-ecosystem/)

Basically if we wiped out the few that carried disease, the ecosystem wouldn’t crash. But there’s a lot of parasites and biting flies that don’t carry diseases, that aren’t of importance to humans, but are still important in the ecosystem. =)

LikeLike

Very interesting and well thought out, but please do not start sentences with “So.” Whenever tempted, try “Consequently” and see how it sounds.

LikeLike

Thanks for the writing tip =) We’re always trying to improve our skills.

LikeLike

I tried explaining this to my mom and she didnt get it. I think i will just let her read your article. Ps i love this site 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks for the support! =D

LikeLike

Pingback: Microcephaly, Zika, correlation, and causation: the science behind CDC’s confirmation of Zika and microcephaly | Ask an Entomologist

Pingback: If I am allergic to honeybees, am I also allergic to other bees? | Ask an Entomologist

Pingback: Lâchés de moustiques OGM et Zika : une relation de cause à effet ? - Meta TV