Co-Written by Joe Ballenger and Nancy Miorelli

Admittedly, this isn’t really a direct user submission per se, but it’s a question which comes up in the entomological world enough to warrant a discussion. Collecting of insects is not controversial amongst entomologists, but seems to strike a chord with many people who are interested in entomology. There’s the perception that entomologists are like big-game hunters and kill insects simply as trophies. Some of the comments regarding this topic can be quite… passionate …and there’s been a lot of heated discussion about why people collect and kill insects.

Anti-collecting comments from Facebook Entomology group, posted under undergraduate collections. First three easily legible comments were chosen.

The reality is a bit different from the perceptions of the posters above. Insects are collected for many reasons, and killed for many more. Taxonomists, the entomologists who describe new species and classify life into systematic groups, often bear the brunt of the blame for insect-killing. Consequently, there’s been a lot of discussion on the internet by taxonomists who explain why collecting is essential to science.

The Karner Blue Butterfly is endangered not because of collecting, but because the city of Albany, New York was built on its specific habitat. However, now that it is endangered, collections are illegal without permits.

Hollingsworth, J & K, Public Domain

Many people are concerned that scientists are helping lead to the destruction of insect species, however the few specimens that scientists do collect for research purposes are not contributing to species loss. A much more pertinent threat to insects is habitat loss and degradation. The posts we linked to are our favorites which explain why killing insects is essential to preserving them, as paradoxical as it may seem.

While taxonomists have done an excellent job of discussing why they collect insects, there’s been a lot less attention to why insects need killed in the course of education, pest control, and research…and that’s what we want to mention in this post.

We want to discuss the reasons entomologists kill insects in order to further the understanding of their biology among the public, to insure the survival of our agricultural systems, insure our own survival, and so we can further our understanding of their biology.

Why discuss insect killing?

Although we love insects, we’ve always been a bit uncomfortable with entomology as a field. Insect biology is extremely cool, because Lovecraftian or Kafka-esque biology comes standard with most species. Some insects eat their own mothers, while others will essentially age backwards to escape starvation. The majority of insects change into completely different creatures when they turn into adults. They’re so far removed from anything we can identify with, that you can spend hours at a time reading about their biology. Whereas most people have golf magazines by the toilet, Joe’s current reading material is about a group of caddisflies which lay their eggs in the arms of a sea star.

Most entomologists are this way, and many of our conversations with our colleagues and co-workers revolve around this sort of stuff because everybody we’ve ever worked with has been as passionate about insect biology as we are. However, a lot of entomologists (ourselves included) must research new ways to kill insects even though we love them as organisms.

So…contrary to what some posters above have said we love insects, but we also research new ways to kill them. Why do we do this?

1.) Entomologists need collections to educate the public

Nancy with a Malaysian Jungle Nymph. This is one of the exotic species we have because of the UGA permits.

In order to reduce the chances of introducing invasive species, there are many restrictions to owning live insects. The University of Georgia, where Joe and Nancy obtained their Master’s degrees, (and where Nancy is still working) recently received permits to have and rear exotic insects. The process to obtain the permits was painstaking and specialty rearing facilities had to be obtained. The only other place in the Eastern United States to have these permits is the Smithsonian museum.

In contrast to live collections, preserved insects are often for sale and there are fewer laws pertaining to the possession and selling of these items. Therefore, with these artfully done collections, we can captivate the curiosity and wonder of children and the public. We can make people who had been fearful, disinterested, or disenchanted with insects become curious, astounded with their natural beauty, and wonder about their remarkable biology. With collections, it is possible for us, as educators and scientists, to visit rural schools in Georgia, USA and show children what insects in rural Africa look like. And while some of this can be done with photography, having someone see with their own eyes a physical specimen the size of their head cannot be replaced by mere images.

2.) Entomologists protect our food supply

Everybody needs to eat. Agriculture is the cornerstone of civilization, and by 2100 we’re going to need to be a lot better at agriculture because there may be as many as 11 billion people on this planet. Unfortunately, agriculture is also extremely inefficient. For every 100 lbs of food which could potentially be harvested, only about 30 lbs is used by consumers. Some of this is waste, but a lot of this is pest damage.

Everybody needs to eat. Agriculture is the cornerstone of civilization, and by 2100 we’re going to need to be a lot better at agriculture because there may be as many as 11 billion people on this planet. Unfortunately, agriculture is also extremely inefficient. For every 100 lbs of food which could potentially be harvested, only about 30 lbs is used by consumers. Some of this is waste, but a lot of this is pest damage.

As an agricultural scientist, Joe looks at the situation like this: Of 100 lbs of food grown around the world, 70 lbs of it is lost along the way on average. Of those 70 lbs, 35 lbs of that is lost in the field before harvest. If every farmer stopped all pest control measures, that number would increase to 70 lbs of food lost before harvest. Without any additional increases in efficiency between field and table, the amount of land needed for agriculture would explode…and that would not be a good situation.

Our biggest animal competitors for food, fiber and shelter are insects. Insects attack food products at various points in the production chain. The examples which spring most readily to mind are those which attack plants in the field, but insects also attack food while it’s being stored. On average, pest and disease losses in the field are between 20 and 40% depending on the crop. In storage, 10-15% of the crop can be lost to pests and the value of the harvest can be dropped by up to 50% due to loss of quality. Complete losses of some crops aren’t uncommon either. Insect infestation also leads to other problems by encouraging the growth of mold that produces aflatoxins, so the losses due to infestation can lead to larger losses due to a loss of quality. While this secondary problem might sound minor, aflatoxins are among the most carcinogenic substances known and are thus one of the biggest and most persistent public health challenges.

Damage to raspberry by D. suzukii. Arrows indicate maggots.

Image from here.

To give one very specific example…you might have noticed the increase price and decreased quality of summer berries this year. That’s because a recent invasive species, Drosophila suzukii, has been scaling its way up the eastern United States. Although it has been in Hawaii since the late 1980’s, by 2010 the fly had been spotted in North and South Carolina, Louisana and Utah in addition to Michigan and Wisconsin. D. suzukii deposits its eggs in summer berries like blueberries, raspberries, and blackberries. The maggots eat the flesh of the fruit, but seem to leave unnoticeable damage until the berry is broken into which exposes many the little wriggling maggots. As you can imagine, this makes the fruit unmarketable. In 2008 alone this fly was responsible for $500 million worth of damage, and some farmers lost 80% of their crop. It’s possible that other countries will refuse to buy our fruit out of fear of accidentally introducing this pest, so there are economic consequences beyond yield loss. In order to protect the livelihoods of these farmers, someone has to figure out how to manage this pest and lots of research has gone into understanding its basic biology.

Agricultural scientists work towards solving these problems by developing better tools for controlling insects. In some cases, insects can be controlled by making the environment really tough to live in through the use of biological controls. In some cases, this isn’t a feasible option and insects need to be controlled through other means. Either way, if we didn’t control insects there would likely be widespread starvation or exorbitant food prices.

3.) Entomologists protect human health

Anopheles gambiae, a mosquito responsible for more human suffering than war.

James D. Ganthany, via Wikimedia commons.

Diseases spread by insects are another huge problem for public health, mostly in developing countries. Every year almost a quarter-billion people contract malaria, and well over half a million die worldwide from the disease. In areas where the disease is found, it can affect every conceivable aspect of life from how people make money to how many children they have. It may be difficult to believe, but malaria was in the US as late as the 1940s. In the year 1934, there were 140,000 cases…and the disease was effectively gone from the US by the early 1950s. A combination of a convenient climate, a good economy, pesticide sprays, and habitat elimination facilitated this. Vector control continues to be an extremely important component of public health measures, because we continue to see malaria imported into the US from travelers.

The story of malaria is an important one, because it demonstrates how important vector control is for maintaining a healthy population. Worldwide, over half the population is at risk for contracting a vector-borne disease. The US is no different, although we are relatively fortunate to have the resources to fight these diseases and a climate which makes them easy to combat. Keeping the populations of disease vectors down is really important.

In short, medical entomologists work to reduce human suffering by killing insects.

4.) Killing insects is essential to studying biological function

Pan trapping is often used to identify arthropod presence in a given area. Here, pan traps are being used to survey for oceanic island arthropod biodiversity

Image from here.

This last one is admittedly the purpose of killing insects which the posters above were talking about. Collecting insects is essential for documenting their presence for a number of reasons. Many insects (as discussed in our first post) are simply too small to see, and a lot of collection methods kill the insects during the course of collection. In addition, a lot of important insect parts need to be extracted for species-level identification. Often the methods required for this aren’t possible to perform on live insects, and when they are they often injure the insects anyways. The posts written by taxonomists give more details about these methods.

There are a lot of research methods which require live field collected insects. Sometimes, you’re interested in biological characteristics of insects in the real world and captive reared insects just can’t be used to answer those questions. Other times, the insects you’re interested in may be impossible or impractical to rear in captivity. Bee research is a good example of this sort of limitation, there are a lot of bee species which can’t be reared in captivity. In bee research, researchers are often interested in real-world responses and this necessitates the capture of live insects from the field. Questions about presence, life history, abundance, and seasonality are all most effectively answered through collection techniques that kill the insects, but otherwise these questions, like questions about native pollinators, could not be answered.

The Bottom Line?

Entomologists are uncomfortable killing insects, and we don’t take it lightly. If we did, we wouldn’t be very good at our jobs. Most entomologists are deeply concerned about environmental issues, and have thought long and hard about why we’re doing what we’re doing. There are a lot of protocols in place to make sure our experiments don’t result in the extinction of species…and we’re constantly working to make public health and agricultural practices more sustainable in the long-term. Although it may seem paradoxical, wise management of insects for public health and agriculture is an environmental concern, and most entomological conservation research would not be possible without killing insects.

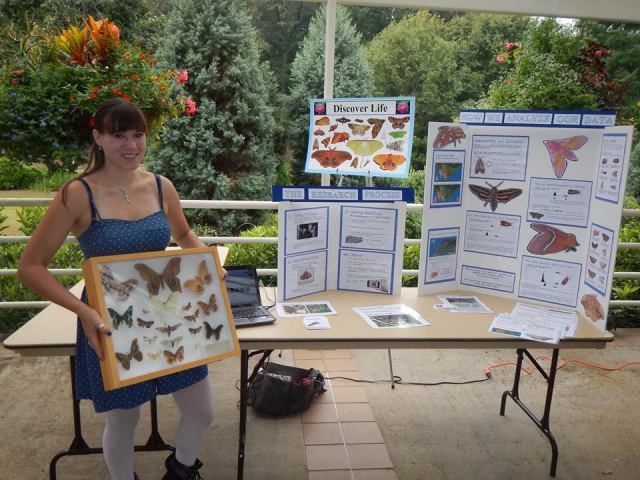

Nancy is displaying the kinds of moths that can be found throughout the world, including the United States, to help get people excited about a moth photography citizen science project through Discover Life.

Correction 1/4/2015: The original article claimed Philanisus plebeius oviposited into the anus of the sea star, whereas the literature states they oviposit into the arms.

Very informative and very useful. I will bookmark this permanently for sharing purposes. Thank you very much 🙂

LikeLike

Great! We’re so happy you liked it ^.^

LikeLike

A lot of this article is just a mixture of nice ideas and plain old “BULLSHIT’. How about asking someone that has ended the lives of billions and billions of insects about this, for a real-life perspective on this subject. The automobiles, airplane, trucks, rail trains kill hundreds of billions of insects daily, There are a host of animals, including birds, reptiles, fish, bats, etc., and other predatory insects as well, that kill hundreds of billions of insects daily, There are companies that sell railcars full of industrial and agricultural chemicals to kill insects, every day of the year across the world. Every person has several insecticides in their homes and use them daily. Every person that switches on a light in and out of their homes, yards, garages, vehicles, buildings, every street lamp by every city, state, and highway, kill hundreds of billions of insets daily and nightly. Like much of the crap written about most things on the www these days, these authors didn’t think about doing the research before writing a nonsensical, grade-school level, personal opinion article about this subject. While I’m sure these two authors are nice, friendly people, their take on this subject is typical of a hastily put together student’s perspective without any actual experience in the real world to back up what they base silly assumptions upon. Yes, I am aware their target subject was entomologists, but to properly do justice, there is much more to include if they want to appear they know what they are speaking (preaching) about and include all the information o properly address The ‘true subject’ of their article..

LikeLike

All of the complaints you have were researched, and directly linked to, but were not rehashed for the sake of brevity. Cars, houses, cities, porch lights, and night time dinner candles kill many organisms, not just insects.

In fact, as we mentioned above, habitat destruction because of roads, cities, airports, and agriculture is one of the most important threats to insects, not – as we clearly state above – collection for scientific purposes. Not to mention all forms of pollution, including light and sound pollution are affecting insects and altering their behavior.

Here is a quote from Piotr Naskrecki’s post that we *linked* in the second paragraph of our post that literally says everything that you just did.

“Every single one of us is guilty of involuntary bioslaughter – we kill thousands of organisms without realizing that we do it. Look into the light fixtures of your house or the grill of your car, they are full of dead insects and spiders. That highway that you drive to work – each mile of it equals millions of animals and plants that were exterminated during its construction (and if you live in an area of particularly high endemism, California or New Zealand for example, its construction probably contributed to pushing some species closer to extinction).”

(The Smaller Majority – Involuntary Bioslaughter and Why A Spider is Dead; http://bit.ly/Ztq9er)

~Your Nice and Well Researched Author

LikeLiked by 2 people

Well, that was quite a steaming pile of gibberish to write in response to a well-written and thought out article.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I am not sure of the conflict here. To me, Vernon and the main article are making the same point – but Vernon seems to think he is disagreeing. Did he read the article? It is not at all the kind of ‘anti-collecting rant’ that would deserve such a strong response..

LikeLike

Pingback: Morsels For The Mind – 02/01/2015 › Six Incredible Things Before Breakfast

Nice! My strepsipteran video (above in your post) also used a killed insect…

Well, mostly. The abdomen of the Polistes was severed to make the video, as even decapitation of the wasp was not sufficient to keep the abdomen in frame. In order to document the emergence, we separated the abdomen and mounted it on plasticine. The emergence was filmed in one room, while Mike Hrabar and I were in the next getting high speed video of male mate-seeking flight.

LikeLike

Pingback: What do mosquitoes (and other biting insects) add to the ecosystem? | Ask an Entomologist

Pingback: Why do we need pest management? « Biology Fortified, Inc.

Pingback: Collecting Tips – The Awkward Inbetween Steps | Ask an Entomologist

Pingback: How do you know if a bug has been discovered before? | Ask an Entomologist

I can say as someone that has worked over 30 years collecting all over the world, performing research using various pescicides and spent the last half of my career as a medical entomologist that killing is still a very serious topic for me. We collect or control for various reasons and it should never be taken lightly. This is the most common question that I get and everyone in the field should be able to articulate an answer in a way that non-specialists can better understand. What is presented here is an excellent overview (not a dissertation like previous commentors would like) to facilitate discussion. This is a blog dedicated to entomology so there is no need to be, nor expect it to be, a peer reviewed journal. Granted, I would like to see more on the medical aspect as it is more than a single disease but a good place to start and build upon.

I support and encourage those doing work that is less destructive but in many cases the older methods are the only way. My experience as a teacher shows that one cannot teach insect identification via PowerPoint and nice pictures, you have to have specimens and lots of them. I can say from my time working with the Smithsonian that DNA can be extracted from older (~100 yrs old) specimens and also that I have shared collected specimens and data with other researchers. Citizen science will only become more prominent, allowing a greater connected community than isolated efforts of universities or research labs. Collections provide so much more than decoration as they serve as a snapshot in time, a comparison point for many other biological aspects that the article pointed out.

I feel the point of the article was missed by some, focusing on the obvious fact that billions are lost from non-research efforts and not the higher philosophical point that there is an intrinsic quality for all living things. It is that quality that many question and ask why we do it.

LikeLike

What worries me is the focus on conservation and species preservation, as opposed to the actual insects themselves. This very same blog has published an article admitting that insects may feel pain or something that resembles it. Do individual insects not, in this case,deserve protection from harm unless it’s absolutely necessary to harm them?

I’m also not convinced that entomology can’t be taught through pictures, as there are hardly any details nowadays that we can’t capture on camera. Even complex phenomena like iridescence can be demonstrated with videos. Would this method of teaching be harder and require more time/effort? Very possibly! But it seems to me that the life and possible “suffering” of an animal (even an insect) is of greater concern than a bit of extra hassle for a human.

I can pretty confidently claim that I don’t have any desire to exaggerate the attributes of bugs —

honestly, I would be SO happy if it were proven beyond any doubt that insects don’t feel any pain. How great would that be? I could kill thousands of them to sell and keep without the slightest moral concern! I could just eradicate them without a care if they’re in my way or bothering me! But it’s really not so clear and I can’t justify acting like they don’t feel anything bad (however convenient it would be) when it’s still very possible that they do.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The comment about big game hunters is way out of line at best.

LikeLike

I live in an area inhabited by over 500 bird species, most of them insectivores. Though it bears testing, I suspect that individual birds of many species eat far more insects than I collect on a single day in the field. It is especially amusing then to hear from bird lovers who decry the collecting and killing of insects.

LikeLike

Hello. I love bugs so sometimes my family says I should be an entomologist. But yes I am concerned about having to kill them. I still have some questions that I cannot find the answer to. The main thing I would like to know is, do you ever get to work with live bugs or only preserved specimens? Do you always have to kill the bugs you study? I’m not worried about the ethics so much as having to work with cool creatures all the time without being able to get attached to them. I especially love spiders, butterflies, crickets, and fireflies (yes I know spiders are not insects). They are not just fascinating but beautiful.

As of right now I am not in college yet and have been applying as undecided. Should I consider being an entomologist or arachnologist? I have many interests, most of which lean more towards literature, the arts, and humanities, except for liking to watch spiders and insects and look up things about them online. (Although I’ve always loved all types of museums and I am taking physics as an elective.) What do you have to study to go into this field, and is it a job a creative type could be happy in?

LikeLike

Hello! I’m glad you’re considering entomology for a job! If you’d like I have a 3 part series about entomology jobs and what they entail. You’ll probably have to kill insects during the semester where you’re learning how to ID them. But there are other research opportunities where you do not need to kill the insect.

Arachnologists usually are formally trained as entomologists first and then later specialize further.

Jobs in Entomology: 3rd Video in a 3 part series.

Hope this helps =)

LikeLike